Okay, so let me tell you about my little adventure with trying to recreate H. Tracy Hall’s diamond synthesis… kinda. Obviously, I don’t have a GE lab or millions of dollars worth of equipment, but I wanted to get a feel for the science behind it.

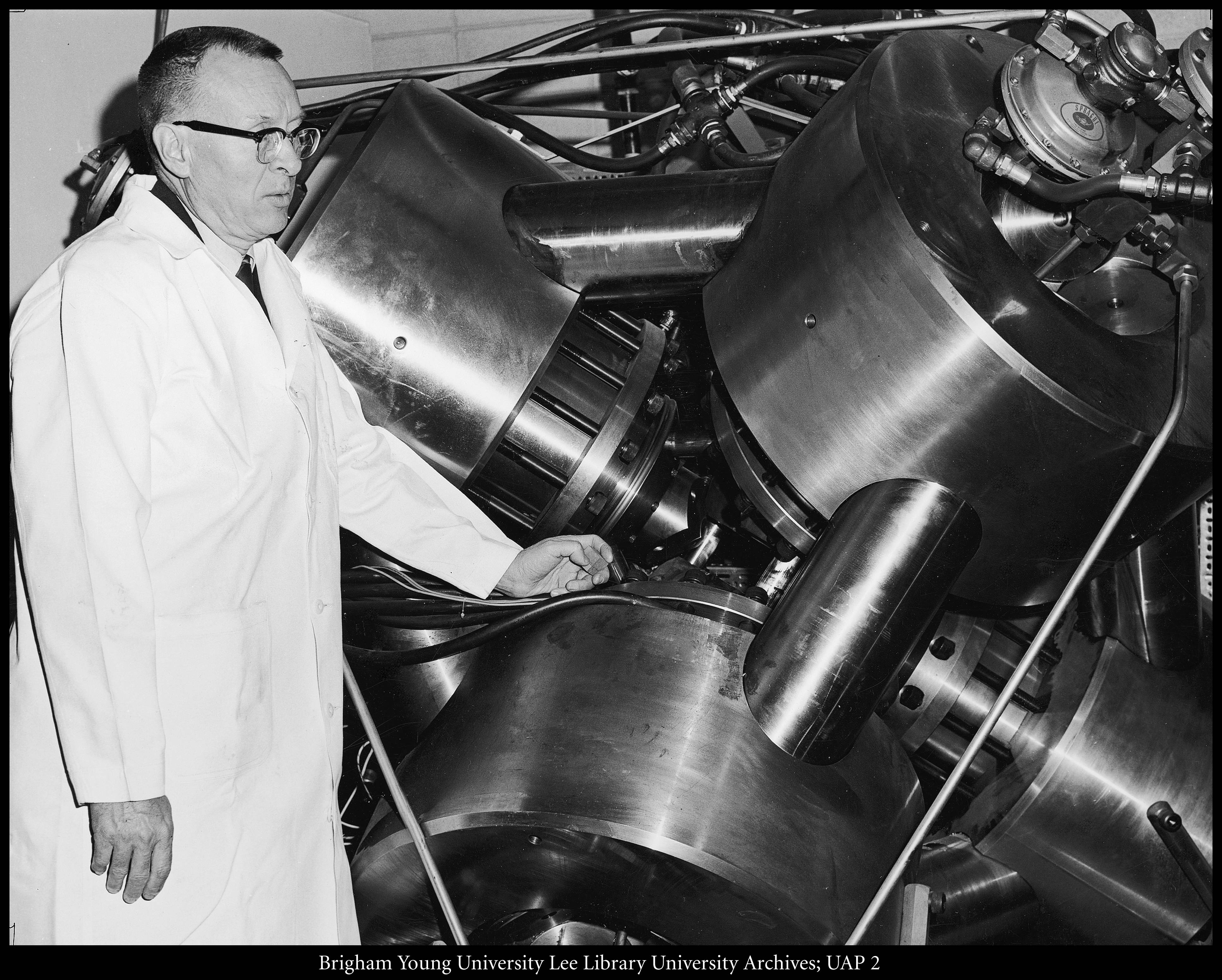

First things first, I did a bunch of reading. I mean, a LOT. I started with the basics: what diamonds are made of, how they form naturally, and then dived into Hall’s work. The key thing I latched onto was the high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) method. He basically squeezed carbon under crazy pressure and heated it up like crazy until it turned into diamonds. Apparently, he also used a catalyst, which helped the process along.

Now, for my “experiment.” I couldn’t actually replicate the pressure and temperature, not even close. But I figured I could try to create conditions that might encourage some interesting carbon structures. My plan was to use graphite (pencil lead – readily available!) and heat it in a controlled environment.

I grabbed a small crucible (a heat-resistant ceramic cup), crushed some graphite into a fine powder, and packed it into the crucible. Then, I used a blowtorch to heat the crucible for a good long while, trying to get it as hot as possible. I know, it’s not the same as what Hall did but bear with me.

After letting it cool down slowly (super important to avoid cracking the crucible!), I carefully broke it open. Inside, the graphite was… still graphite. Surprise! But, and this is a big but, it did seem a bit denser and more compact than before. Almost like it had been slightly sintered together.

Okay, so no diamonds. But I wasn’t expecting any. The point was to understand the process. I learned a ton about the challenges Hall faced, the ingenuity he used, and the sheer scale of what he accomplished. He was working at pressures of over 100,000 atmospheres! That’s insane!

Next, I tried a different approach. I remembered reading about how some metals can act as catalysts in diamond formation. So, I mixed the graphite powder with some powdered nickel (I got it from a science supply store, don’t ask). Then I repeated the heating process with the blowtorch.

Again, no diamonds. But this time, after cooling, the material inside the crucible was different. It had a metallic sheen to it. It was like the nickel and graphite had partially fused together. It was a bit harder and more brittle than just graphite. I even tried scratching a piece of glass with it, but it didn’t leave a mark. So definitely no diamonds.

What did I learn?

- Making diamonds is REALLY hard. No surprise there.

- Even without the proper equipment, you can still learn a lot by trying to understand the science and experimenting on a small scale.

- H. Tracy Hall was a freaking genius.

It wasn’t a scientific breakthrough or anything, but it was a fun and educational project. It gave me a much deeper appreciation for the science and engineering behind diamond synthesis. Plus, I got to play with a blowtorch, so that’s always a win.

Maybe next time I’ll try something with chemical vapor deposition… but that’s a story for another day.